Leaning into this race a few months out, something strange began to happen: I started experiencing frequent tight spasms in my chest every time I ran. I was training regularly in the LA area, and about ten minutes into each run, my chest would tighten up, almost as if it were squeezing the life out of my heart. It was unsettling—I’d have to stop completely and wait about ten minutes before I could start moving again. I had no idea what was causing it, but it definitely scared me each time.

The pain would go away after resting, so I got it checked out, but nothing showed up. No issues with my chest or heart. Somewhat relieved but still mainly puzzled, I decided to keep training. I chalked it up to anxiety, especially considering the stress I was carrying during those early months of sobriety, this was not something unfamiliar entirely for me.

At that point, saying I was still figuring out how to train would be a polite phrase as I had little to no idea how to prepare for a 100-mile race. But I managed to get my weekly mileage over 100 miles for two consecutive weeks, which felt like a significant accomplishment. I was stacking half-marathons in blocks of three, followed by a lower-mileage day, then two longer days in the mountains outside of LA. Without a clear structure and mostly guessing, I’d be lying if I said the repetition and uncertainty didn’t start to wear on me. The grind was getting to me, both physically and mentally.

Soon enough, I found myself turning the key and making the drive from LA to Auburn. Along the way, I picked up my mom in Sacramento, who had flown out to crew for me during the race. This was a special homecoming for her, as she’s a former Western States 100 winner, and the Canyons course intersects with the Western States course in several places. Both races finish in Auburn, making the experience even more meaningful. I’ll certainly write more about this connection at some point. We soaked it all in together, exploring parts of the course before race day, while I tried my best to calm my nerves. I went out for a couple of shakeout runs, and, sure enough, the chest pain was still there.

The night before the race, I struggled to sleep, desperately trying to calm my body and mind. I searched for ways to soothe myself, but nothing seemed to work. After what felt like hours of tossing and turning, I finally decided to stop fighting it. I put down the mental shovel I’d been using to bury my feelings and admitted to myself that I was nervous and afraid of the challenge ahead. Almost immediately, the nerves disappeared. I didn’t understand it at the time, but I had been denying myself the right to feel anxious and uneasy about this race for months. There’s a fine line between not letting fear consume you and acknowledging it, but in this case, I had been expending so much mental energy trying to push it away. Accepting the fear made all the difference.

Starting this race, like many others, felt surreal. You spend so much time thinking about it, training for it, and planning, and then suddenly it’s right in front of you, real and tangible. The weather forecast wasn’t promising—rain, cold temperatures, and overall rough conditions were expected. As I was shuttled to the starting line with the other 100-mile runners, my mind ran through the race plan I had meticulously laid out, reviewing my nutrition benchmarks and pacing strategy. This was the first time I had put real effort into creating a detailed plan, and I was determined to stick to it.

I positioned myself near the back-middle of the starting group, trying to stay warm as light rain fell and the morning chill seeped into my bones. When the race began, I consciously pulled back on my pace, determined to take it easy from the start. Within the first thirty minutes, the light rain turned to hail, and the trails quickly transformed into small rivers. My feet were soaked almost immediately, and my lightweight rain jacket became saturated within the first hour.

The terrain was relentless from the start—steep, choppy climbs and descents that would set the tone for the next day and a half. By the time we reached mile ten, heading toward Devil’s Thumb, the rain had eased, but the trails were still a muddy mess. I took a conservative approach on the descent and climb, as the trail was essentially a mud bath.

The weather remained unpredictable. As I focused on reaching the mile 24 about aid station, where I would see my crew for the first time, the sun came out in full force. It created a hot, humid environment as I descended into the canyons and then climbed back out toward Michigan Bluff. But just as I reached the top, the weather shifted again—overcast skies gave way to torrential rain, seemingly timed perfectly with my arrival at the aid station. I made a quick stop, grabbing the baggie of supplies I had prepared beforehand and swapping my soaked lightweight jacket for a heavier-duty raincoat my crew had ready. It was clear that I’d need it for whatever was coming next.

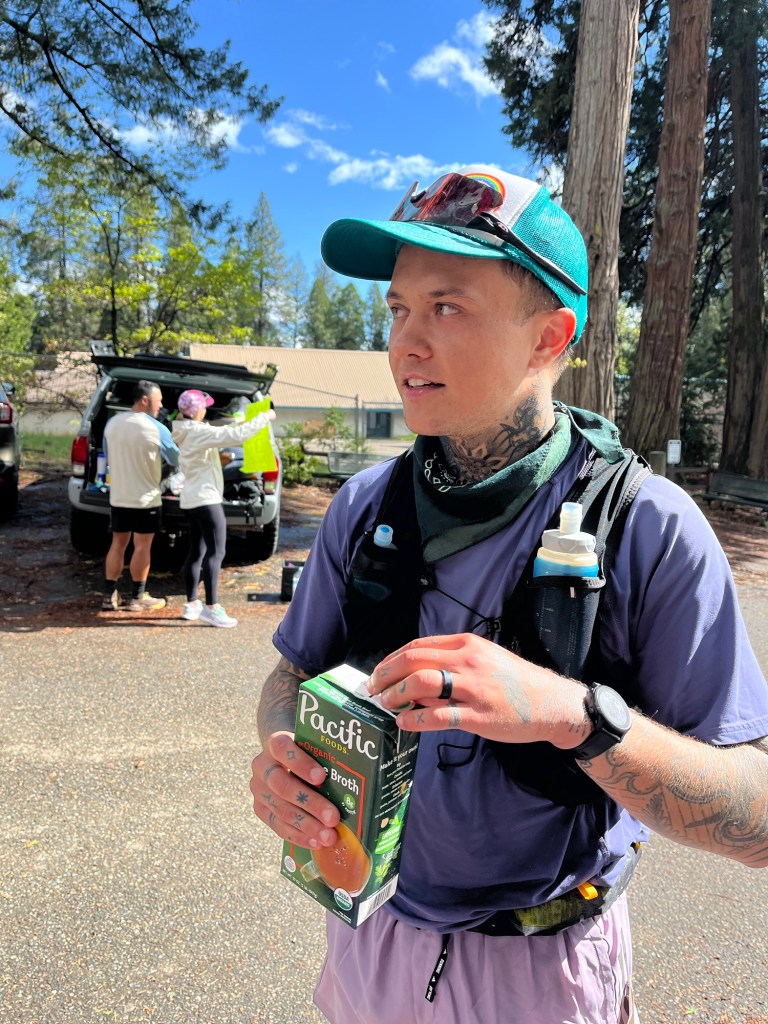

Up until this point, I was managing pretty well. I was sticking to my nutrition plan, mentally engaged, and in good spirits. Surprisingly, my chest wasn’t giving me any issues, but I didn’t dwell on it too much. The stretch from Michigan Bluff to Foresthill passed quickly, marked by another wild swing in weather—from cold rain to hot, humid sun. Reaching Michigan Bluff meant I had hit the 50K mark, and I was right on schedule around six hours. After gearing up and grabbing what I needed, I set out again, knowing I wouldn’t see my crew for another twenty miles.

I left the aid station feeling strong and confident, pushing the pace. I quickly found myself alone, having lost the group of runners I had been with earlier, but I didn’t mind. The first 16 miles of this stretch flew by. The conditions were stable, the environment felt welcoming, and I was taking in calories with ease. It was smooth sailing until I reached the bottom of a large canyon, right before the climb to Drivers Flat. That’s when the weather shifted once again—sudden downpours, thunder, and lightning. As someone who’s always had a fear of lightning, I tried to keep my head down and push through without thinking too much about it.

I rolled into Drivers Flat at the halfway point just as darkness was setting in. I took the opportunity to change clothes, grab my next set of supplies, and throw on my headlamp. I still felt pretty good at this point and headed out onto relatively easy terrain. I made solid progress to No Hands Bridge, but from there, the course took a sharp turn up a brutal, steep trail that felt more like climbing giant steps. It was hellish, and I struggled up the climb miserably. This was a turning point for me, where I could feel the wheels starting to come off.

The next several miles became a bit of a blur. I reached an aid station that also served as a loop point for runners, but by this time, my focus had started to slip. My foot strikes were less controlled, my body temperature was dropping with the cooler night air, and I began to fall behind on my nutrition. I found myself alternating between walking and running, and my mind started drifting to random places. The aid station stop was brief, just enough time to gear up before heading out again, not realizing how close I was to the edge. The wheels were beginning to come fully off, and I was about to find out what that really meant.

In my mind, I imagined I’d be out on this loop for maybe an hour and a half at most. It ended up taking me three hours to make it back to the aid station. The terrain was surprisingly runnable, but I had no running left in me at that point. I had stopped alternating between walking and jogging and was now just trying to maintain a slow shuffle. Unfortunately, I started this loop alone and ended up doing almost the entire thing with no one around me.

By the time I hit the halfway point of the loop, it was close to 4 a.m., and the exhaustion of the day hit me like a brick wall. All of a sudden, I could barely stand, let alone keep my eyes open. I was forced to take a dirt nap, leaning against a tree for what felt like just a minute or two. When I got up, I nearly face-planted as my body gave out, but luckily, I managed to glide smoothly to the ground and passed out. Sleep overtook me almost instantly, and though it seemed brief, it felt like it could have been hours.

When I pulled myself off the ground, I felt some semblance of a second wind. My body was more alert, ready to move again, but my mind was still foggy and disoriented. Caught between exhaustion and alertness, I began to hallucinate heavily. Every time I lifted my head, my headlamp would catch what looked like random people charging toward me through the tall grass. I would scream—part fear, part confusion—but there was no one there. Thankfully, as the sun began to rise, my mind started to wake up too, tricked by the daylight into shaking off the hallucinations. But a new problem emerged. I had been dealing with minor knee and shin pain off and on, but at some point during this loop, it escalated into a level of pain that felt almost biblical, coming out of nowhere, just like the exhaustion had. I hadn’t experienced anything like it before and didn’t really know how to handle it. My only focus was on getting back to the aid station.

Pulling into the final crew-accessible aid station, a strong voice in my head told me to drop out. The pain in my shins was excruciating, and every step sent a wave of distress through my body. I sat down by the car and asked my mom to clear the back seat so I could lie down, but she wisely refused. Instead, she handed me the last pre-packed bag I had prepared and sent me back out on the course.

The last twenty miles were, thankfully, some of the most beautiful, and I was able to appreciate them—albeit at a snail’s pace. The shin pain was relentless, but I kept moving. I had planned to turn on some music after leaving the aid station, but when I went to unlock my phone, it told me it would be locked for three hours. Apparently, it had been trying to unlock itself in my waist belt, leaving me without that music as aid for most of this final section. Felt fitting in a way.

The last part of the course consisted of a long downhill, followed by a loop, a long uphill back from where you came, another downhill to No Hands Bridge, and then the final climb back into Auburn. To get myself running again, I had to gradually shift gears. I’d start walking, progress to a power hike, slowly pick up my legs, and eventually manage something resembling a run. The whole process took about ten minutes, and I could maintain that “run” for maybe another ten minutes before needing to power down again. I cursed often during this stretch—so often—hanging on by threads.

I didn’t find out until later that my shin pain was not only due to shin splints but also from running through poison oak, which caused dramatic swelling in my legs. Mentally, it took everything I had to stay focused and not fall into despair, though I did fall several times. Seeing a group of runners I had been with hours earlier ascending a climb I wouldn’t reach for a few more hours was demoralizing. Near the descent back to No Hands Bridge, I decided to give whatever I had left. I started to run, truly run, for the first time in what felt like forever. I couldn’t sustain it long, but I did manage to get some distance. Tears welled up from some deep, unknown place, a rawness I had never felt before. I was tapping into a primordial part of myself. I crossed the bridge, ran as much of the final climb as I could, and finally reached the top, where I saw my mom.

As soon as I saw her, I broke down in tears. I had so much I wanted to tell her, but I couldn’t find the words. She was crying too and simply said, “It’s okay, I know. You don’t have to explain.” I still feel like I have so much to tell her about that day, but some level of inability exists to really tap into what happened out there. And I think that’s okay. These are the questions I may never answer, and maybe I don’t want to. Running these races makes realize it is more important to ask the right question at the right time than find any definitive answer more often than not. If I could give some nice packaged reply in that moment or now months later, these experiences wouldn’t carry the same magic. The misery wouldn’t be so meaningful, and the success wouldn’t be so satisfying. We walked and jogged the last mile together. I crossed the finish line in just over 30 hours. After the race, my mom went to talk to Gordy Ainsleigh, an old friend of hers who had just finished the 50 K race. We shared some congratulations and told him I’d completed the 100-miler along with telling him my time. He paused for a moment and said, “Well, you’ve got some big shoes to fill.”

Leave a comment